CHILD POVERTY REPORT CARD 2018: CAUTIOUSLY OPTIMISTIC

BC CHILD POVERTY IN 2016

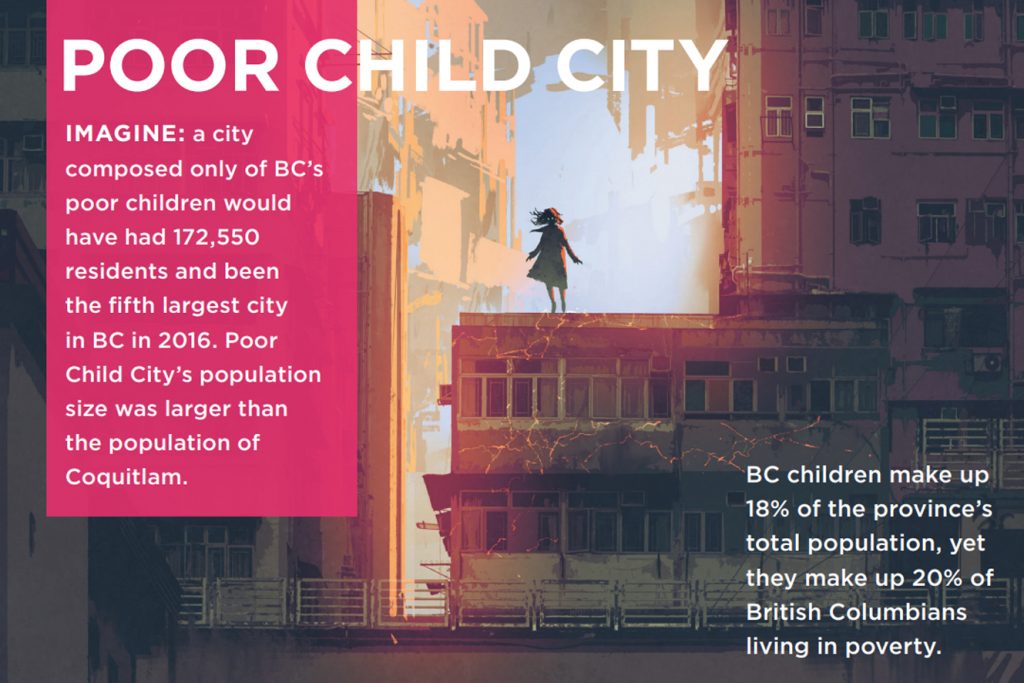

Data reveals that once again far too many children in British Columbia are growing up in poverty. One in five children, or 172,550 children and youth, are growing up in poverty. And many are growing up in deep poverty — up to $13,000 below the poverty line. This includes poor households where one or more parents are working.

Data reveals that once again far too many children in British Columbia are growing up in poverty. One in five children, or 172,550 children and youth, are growing up in poverty. And many are growing up in deep poverty — up to $13,000 below the poverty line. This includes poor households where one or more parents are working.

Due to systemic discrimination and other factors, the situation is even worse for some groups of children. Indigenous children, new immigrant children and children in visible or racialized minority groups all have much higher poverty rates than the BC average.

In 2016, half of BC’s children in lone-parent families were poor, over four times the 12.5% rate for their counterparts in couple families. And 82% of lone-parent families were female-led, with median annual incomes that were just 69% of male lone-parent families.

These statistics reflect the continued growth of income inequality in our province and across Canada. They reflect decades of allowing and facilitating the massive accumulation of wealth in the hands of fewer and fewer individuals, while thousands of children and youth are deprived of the security, supports and opportunities they need to thrive. They also reflect the growth of precarious work and stagnating wages as families face soaring costs for essential living expenses such as housing, food, child care and transportation. They reflect the impact of tax systems and a social safety net that have failed to respond to this growing unfairness and inequality.

It is profoundly disappointing that our 22nd annual BC Child Poverty Report Card still shows one in five (172,550) BC children are poor.

While the situation for so many children and their families remains unacceptable, over the past few years both federal and provincial governments have taken steps in the right direction.

Specifically, the implementation of a more generous federal Canada Child Benefit in 2016 is already making a difference to the depth and rate of poverty for families with children who receive it.

In 2018, both the federal and provincial governments either tabled or legislated poverty reduction plans. In November, the federal government introduced Bill C-87, an Act respecting the reduction of poverty, setting aspirational targets to reduce Canada’s overall poverty level 20% below the 2015 level by 2020 and 50% below the 2015 level by 2030.

This fall, the BC legislature unanimously passed the Poverty Reduction Strategy Act compelling the Minister of Social Development and Poverty Reduction to develop a strategy to reduce and prevent poverty. The legislation sets out targets to reduce poverty by 25% among all persons and by 50% for those under 18 years of age over a five year period beginning on January 1, 2019.

While these efforts are not insignificant, the federal strategy must be measured against the fact that no new spending was attached to the catalogue of mostly existing initiatives that require varying degrees of implementation.

“There is nothing that is more significantly associated with the removal of children from their families — than poverty.”

— Dr. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond Testimony, National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, October 4, 2018

In the same vein, the passage of the BC government’s poverty reduction legislation was welcome news but implementation strategies, to be announced in 2019, cannot come soon enough for children and their families struggling with insufficient income and high costs of living.

In the same vein, the passage of the BC government’s poverty reduction legislation was welcome news but implementation strategies, to be announced in 2019, cannot come soon enough for children and their families struggling with insufficient income and high costs of living.

Impacts on child poverty related to the BC government’s new Child Care Fee Reduction Initiative and the Affordable Child Care Benefit launched this year are not captured in this report card. However, we know that lowering costs, as the province transitions to a universal child care system, will greatly assist low-income families with preschool aged children, in many cases removing a barrier to going to work.

IMPORTANT CHANGES IN THE MEASUREMENT OF POVERTY

In 2018, several important changes occurred in the measurement of poverty in Canada.

The Market Basket Measure (MBM) was adopted as Canada’s first Official Poverty Line by both the federal and provincial governments. Secondly, Statistics Canada updated its approach to how income rates are calculated within the Low Income Measure (LIM) — a measure that First Call and Campaign 2000 partners across the country have been using to report on child poverty for many years.

The 2018 BC Child Poverty Report Card continues to use the LIM as a measure of child and family poverty. Child poverty rates calculated through the new approach — Census Family Low Income Measure (CFLIM-AT) or LIM — are consistently about 3% higher than those derived using the previous methodology on a year-over-year basis.

First Call and Campaign 2000 believe this change has produced a more accurate picture and that the extent of child poverty was previously underestimated. The change highlights how the omission of some groups with higher rates of poverty from source data may bring down poverty rates overall.

Where this report includes historic annual rates, the new CFLIM-AT calculations replaces those published in previous BC Child Poverty Report Cards.

This fall, Statistics Canada launched a public consultation on what items should be included in the MBM. Once this process is complete, First Call and Campaign 2000 partners will revisit the merits of both MBM and LIM measures. See Appendix 2 for more information about the MBM and LIM.

We know poverty in a wealthy province and country is a violation of children’s rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The federal poverty reduction strategy, Canada’s new national housing strategy and BC’s new poverty reduction act make references to human rights. The new national housing strategy is described as a ‘rightsbased approach,’ and the BC act notes commitments to Indigenous peoples including the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

First Call is cautiously optimistic about governments’ plans but we will not lose track of what matters. Today, as has been the case for many years, one in five children in BC are growing up in poverty. The real test of governments’ plans to reduce child poverty is whether or not it does just that. This year’s Child Poverty Report Card indicates we have a long way to go in BC to ensure all children and youth have what they need to thrive.

First Call is cautiously optimistic about governments’ plans but we will not lose track of what matters. Today, as has been the case for many years, one in five children in BC are growing up in poverty.